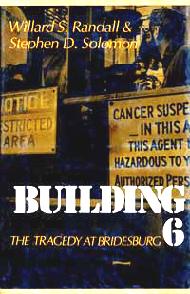

Building 6: Chapter One

They’re gone now, that close-knit clan of chemical workers from the Bridesburg plant of the Rohm and Haas Company in Philadelphia. Many of them died of cancer from mixing a lethal chemical on the job, a little-known chemical called bis-chloromethyl ether (BCME) that disappears in production but nonetheless has killed more than fifty workers in the United States, Germany, and Japan.

They’re gone now, that close-knit clan of chemical workers from the Bridesburg plant of the Rohm and Haas Company in Philadelphia. Many of them died of cancer from mixing a lethal chemical on the job, a little-known chemical called bis-chloromethyl ether (BCME) that disappears in production but nonetheless has killed more than fifty workers in the United States, Germany, and Japan.

A few of the men who worked with the deadly gas at Bridesburg got away alive.

Some, like Reds Olcese, transferred to less dangerous, lower-paying jobs around the vast, ninety-building, hundred acre plant along the Delaware River. Others, like Bob Mason and Hank Janik, left the company altogether to seek safer jobs as policemen and plumbers to support their houses full of children.

But most of them stayed doggedly on, producing tons of frothy little beads inside a crude, corrugated tin and cement block building. One by one, over fifteen anxious years, they succumbed to searing, wracking, respiratory cancers caused by the chemical that they were mixing night and day. Eventually, they dragged themselves home to die in their narrow row houses or in hospitals heavily endowed by the profits of their company.

For a long time, they thought—indeed they were led to believe—that they had smoked themselves to death, shagging cigarettes on breaks in the plant locker room or in the few hours they had at home between double shifts and seven-day work weeks. Nearly everybody—plant doctors, their buddies, their wives—said it was the cigarettes that were killing them.

As their names dropped off the work rosters one by one and their grim death notices and ID photos went up on the bulletin board outside the company cafeteria, in turn the men mourned each other briefly, went to each other’s funerals, volunteered as pallbearers to carry each other’s caskets, and lowered them gently into their graves.

In some cases, entire circles of men who had come to be as close as members of a family were decimated, whether or not their deaths could eventually be tied to BCME exposure.

When Cyril J. Engelhard succumbed to cancer at age 54 in the spring of 1956, his brother-n-law, Tom Hills, helped his co-workers heft the coffin to its niche behind the sooty red sandstone arches of Most Holy Redeemer Cemetery, just down the street from the main gate of Rohm and Haas. Cyril, whose death was never officially attributed to BCME by the company, had worked together with Hillsey, as they called him, and, according to his niece, with Joseph “Reds" Olcese, William “Buzzy” Buzydlowski, Paul Auman, Art Parfitt, and Leonard “Beans” Bean.

They ate deviled crabs and deviled clams by the bucket and sipped cans of beer in Hillsey’s big backyard across the street from the plant while Hillsey’s seven daughters crawled over their cars, sweeping out, washing, and simonizing them. They got together with Reds Olcese’s younger brother, Larry, and the other members of the BCME crew, Chappie Keplin and Joe Karcher, Bob Pontious and Matty Werynski and Mike Troyanoski, around the corner from the plant at a place they used to call Johnny’s U-Bar. There, almost every Friday from four in the afternoon often until midnight, every payday they drank Rolling Rock beer and threw darts and shot shuffleboard, shouting jokes and tall stories and jibes over the throbbing noise of the jukebox.

“They were so close,” remembers Larry Olcese’s daughter, Joann. “They’d have such a good time. And on Saturday morning, Chappie would be on the phone to my mother apologizing for keeping Daddy out so late and promising he’d never do it again. Ma would laugh and say, ‘Sure, Chappie, sure,’ and the next week they’d do it all over again.”

“There never were such buddies,” adds Hills’s daughter Carolyn. “They hunted and fished together, they fixed each other’s houses and cars, they’d do anything for each other. If one was broke, the others chipped in to help. If one got sick, they gave blood. They just don’t make buddies like that anymore...”

In the meantime, Art Parfitt, only thirty-three, had died on April 29, 1963, yet another member of the BCME crew, according to the company, to die of lung cancer. Hillsey and Reds and Buzzy helped to carry his coffin down the steps of Ascension Church to the hearse for the ride to his grave. Their buddy, crew-cut Paul Auman, could not help them this time: one year later, on May 11, 1964, he died of lung cancer. Hillsey and Buzzy and Bob Pontious and the others rode with his body and buried him.

Nine months later, they buried Buzzy Buzydlowski, too. He died on February 24, 1965, the next member of the BCME crew to succumb to respiratory cancer, but by then Hillsey was too weak to take much of the weight of the coffin. He had lost a lung and all but two ribs on his right side.

And then, a few days before Easter 1965, Reds and Beans and the others who had taken Auman’s and Parfitt’s and Engelhart’s and Buzydlowski’s places in the BCME crew were carrying Hillsey himself to his grave. Eight years later, Beans would join them, dead, too, of lung cancer.

Occasionally, at the last ritual, one of the widows would break down. In August 1969, at the funeral of Matty Werynski, his widow, Angela, turned to Joe Karcher, one of his pallbearers from Building 6, and sobbed, “Why don’t you get the hell out of that place. The same thing is going to happen to you.”

But men like Karcher, only thirty and apparently fit, the father of two young children, needed the job. He couldn’t see his way clear to quit. He’d refused to let his wife, Loretta, work so he could finish college, and now his son, Joey, was beginning to talk about wanting to go to college. So Karcher tried to ignore the deaths of the men around him. He piled on the overtime.

When they wheeled Joe Karcher into his last company picnic at West Point Park in Clementon, New Jersey, a few months before he died, he was emaciated, down from 175 to 110 pounds. His skin had taken on a sickly greenish cast. And when he died of the cancer four months later at age thirty-seven, his buddy, big, tough Bob Pontious, softened for a moment, turned to his wife, Marie, with tears in his eyes, and murmured, “Maybe I’ll be next.”

And he was.

Copyright by Stephen D. Solomon and Willard S. Randall. All rights reserved. This material may not be used without prior permission of the author.